History of Cleveland’s Diversity & Inclusion and Community Benefits: Lessons Learned

Athena Nicole Last

Over the past 50 years, local government and business leaders in Cleveland have implemented several ordinances, policies, and programs seeking to promote diversity, inclusion, and equity (DEI) within the construction industry and urban redevelopment. These DEI efforts have had a significant impact on the urban planning process in the City of Cleveland and led to the creation of Cleveland’s Memorandum of Understanding Regarding Community Benefits and Inclusion (MOU) or what is commonly referred to as a model Community Benefits Agreement (CBA). In this article, I share a detailed account of Cleveland’s model CBA and explore DEI initiatives (both prior to and post MOU) to provide historical context for the potential creation of the City of Cleveland’s Community Benefits Ordinance (CBO). Using information collected from interviews and other publicly available sources, I describe the negotiation and implementation processes and outcomes of Cleveland’s MOU. I also examine 5 development projects (post-agreement), that instead of abiding by the MOU, employed an alternative community benefits plan. I highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the agreement along with other DEI efforts, so local government and other relevant stakeholders can learn from these examples when creating Cleveland’s first CBO.

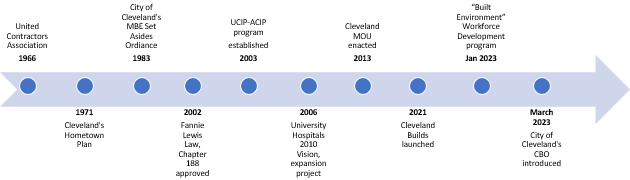

Timeline of Cleveland’s MOU & Other Related Activities

Foundation for Cleveland’s MOU

The impetus for Cleveland’s model CBA was due to the political will to combat persistent racial and ethnic disparities as well as discrimination within the construction industry. Government and industry leaders implemented several DEI initiatives, which laid the groundwork for Cleveland’s MOU and other more recent actions. Such politically led efforts to advance DEI include:

1966- United Contractors Association The Building Trades Employers Association (BTEA), the Cleveland Building and Construction Trades Council, and 40 Minority-owned Business Enterprises (MBEs) contracting companies creating the United Contractors Association to assist workers of color in entering apprenticeship programs.

1971- Cleveland’s Hometown Plan The establishment of Cleveland’s Hometown Plan required a certain percentage of people of color on federally funded projects of $500,000 or more, funding for apprenticeship training programs, assurance that unions made good faith efforts to admit 2,500 persons of color into the trades over five years (500 each year), and the formation of an oversight committee.

1983- Cleveland’s MBE Set Asides Program The enactment of Cleveland’s MBE Set Asides program, which required 30% MBE and 10% Female-owned Business Enterprise (FBE) goals and provided BTEA funding for educational and training programs for MBEs and FBEs. Since the 1980s, the courts have maintained mixed decisions on the legality of MBE Set Asides programs. This has led to the State of Ohio, Cuyahoga County, and the City of Cleveland discontinuing Set Asides programs, and local municipalities creating various iterations to meet legal regulations, such as conducting disparity studies to determine whether a Set Asides program is necessary.

2002- Fannie M. Lewis Law The Fannie M. Lewis Cleveland Resident Employment Law, approved in 2002 but enacted in 2003, required City of Cleveland residents to perform 20% (of which 4% are low-income residents) of total work force hours on City projects costing a minimum of $100,000. Contractors who failed to meet the requirement were penalized 1/8 of 1% of the contract for each percentage point missed. In 2016, H.B. 180, a bill to ban local governments from enacting laws requiring a certain percentage of workforce hours to be completed by local residents in construction, passed in both the House and Senate and was signed into law by Governor John Kasich. In 2016, the City of Cleveland sued the state because the City argued that the law violated home rule laws. The City of Cleveland won in the Cuyahoga County Court of the Common Pleas and Ohio’s Eighth District Court of Appeals, but lost in the Supreme Court of Ohio. In a 4-3 decision, in 2019, the court ruled that the state’s home rule superseded local authority because all construction residents, including their welfare, are affected. Regardless of the state’s actions, the Fannie Lewis law proved successful and increased the number of Cleveland residents and workers of color who were employed in the trades.

2003- Construction Industry Advancement Program – Construction Industry Service Program-Apprentice Skills Achievement Program (UCIP-ASAP) In partnership with the Cleveland Building & Construction Trades Council, Construction Employers Association (CEA) (formally BTEA) enacted the UCIP-ASAP to provide funding for pre-apprenticeship programs, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) training, drug testing program, and other educational and training services for employees and contractors.8 It was reported in 2011, that the program brought in roughly 30 Cleveland residents per year or roughly 300 City residents in total.

2006- University Hospitals’ 2010 Vision, Expansion Project University Hospitals (UH) created a 5-year strategic investment plan of over $1 billion, referred to as Vision 2010. The plan included a construction expansion project estimated to cost $750 million. UH negotiated, what is referenced as a Project Labor Agreement (PLA) between the Cleveland building trades, while the City of Cleveland acted as an intermediary. In reality, the agreement is similar to a Community Workforce Agreement – Project Labor Agreement (CWA-PLA), which means it comprises employment opportunities for local and disadvantaged residentials in addition to typical PLA community workforce provisions. The CWA-PLA benefits included: a 20% City of Cleveland resident hiring goal, 15% MBE and 5% Female-owned Business Enterprises (FFBE)contracting goals, 80% local and regional procurement, increased funding for a pre-apprenticeship program at May Hayes high school, and the hiring of a third-party consulting agency to monitor implementation. UH held several community meetings to share progress of CWA-PLA goals and collaborated with the community to overcome some of the challenges to achieving goals. All goals were met, except for the targeted hiring goal. Of its total workforce, UH hired 18% City residents, which means 5,200 construction and 1,200 permanent jobs ($500 million in wages) went to Cleveland residents. UH achieved 7% FBE and 17% MBE contracting goals, and 92% goods and services were purchased from local Northeast Ohio businesses.

These initiatives set the precedent for changing how business was done in Cleveland and were catalysts for the enactment of the MOU.

Cleveland’s MOU

Negotiation Process

There was significant support and pressure from political leaders and other industry leaders to provide more economic opportunities for low-income individuals and people of color living in the City of Cleveland. Between 2010 -2011 the Greater Cleveland Partnership (GCP) commissioned a study on barriers for MBE contractors, which showed low MBE contractor participation on development projects. This influenced the City’s decision to host a summit on DEI initiatives related to the construction industry and also led to discussions around creating a MOU. Beginning in 2011, local government stakeholders did significant research to understand the entire process of the CBA from negotiation to implementation, monitoring, and enforcement. Cleveland political leaders also sought advice from community-based organizations in Los Angeles who negotiated one of the first CBAs in the nation, the LA Live CBA. Other key stakeholders who were involved in the initial steps of the MOU include were MBE owners, CEA, and various social institutions (such as hospitals, colleges, and secondary schools). A Cleveland MBE owner suggested that the three pillars for any CBA are local contracting opportunities, employment opportunities for local residents as well as apprenticeship and workforce development training. While some CBAs do include other provisions, such as affordable housing and green space, most CBAs prioritize securing economic opportunities for MBEs and workers of color, like Cleveland’s MOU. Due to political leaders leading the effort, there was no community outreach to involve residents in the process of creating a model CBA. The MOU operational effort led by the GCP, waned as it lacked significant construction industry leadership involvement (Cleveland Building & Construction Trades Council nor the employer associations (CEA, Mechanical, Plumbing, Electrical, Sheetmetal, Painters, etc.) were engaged). This is significant shortcoming as most of the construction work performed in Cleveland is performed by the union trades and employers, making their leadership and involvement critical to the success of programs.

Initially, there were concerns about targeted hiring goals, such as setting aside a certain percentage of work hours for residents, as a potential threat or competition to union work. Political leaders guaranteed prevailing wage for construction projects (where permissible). After over a year of negotiations the MOU was signed in 2013 by the following signatories: the City of Cleveland, MBEs (e.g., Ozanne Construction Company, McTech Corporation, Coleman-Spohn Corporation, JWT&A LLC), CEA, Hispanic Roundtable, Hard Hatted Women, Cuyahoga Community College, Greater Cleveland Partnership, Urban League of Greater Cleveland, Cleveland Metropolitan School District, Cleveland Building and Construction Trades Council (CBTC), and several institutional actors (e.g., Cleveland Clinic, Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C), etc.).

The MOU benefits included:

- a workforce demand study,

- 15% MBE, 7% FBE, and 8% SBEs contracting goals,

- 20% Cleveland resident hiring goals for predevelopment and construction,

- Contractors pay workers prevailing wage,

- pre-apprenticeship programs for high school students and adults

- full-apprenticeship programs,

- mentor-protégé relationships,

- assistance to contractors and other relevant parties to meet apprenticeship and pre-apprenticeship utilization goals,

- quarterly workforce reporting, and

- a Construction Diversity and Inclusion Committee.

Implementation Process

GCP, Northeast Ohio region’s Chamber of Commerce, was selected to oversee the implementation of the agreement. To strive for an effective agreement and to track the progress of reaching its goals, six committees were established and expected to meet quarterly. These include the executive sub-committee, owners’ outreach, data reporting, pre-apprenticeship and training, sub-contracting, and community engagement. The committees, which were represented by industry leaders, discussed barriers in achieving workforce and entrepreneur goals, and worked together to provide solutions. Due to the MOU agreement having aspirational goals the committee has limited authority to enforce them. Another constraint had to do with reporting. According to a government official, since contractors, who signed the MOU, went “above and beyond what they would ever legally be obligated to do in an effort to strengthen their community and provide additional benefits on the project,” GCP and the committees were unable to push owners and contractors to submit monthly reports and/or provide specific detailed and consistent data. If contractors are not required too, they will be unmotivated to do additional work, like reporting, even if it may be the right thing to do. When an agreement is strictly voluntarily, contractors must be morally persuaded to act in good faith, as a few stakeholders mentioned.

Outcome

Several Clevelanders found that the MOU “lacked teeth” because of a lack of enforcement, monitoring, reporting, and compliance mechanisms. The data was inconsistent, inaccurate, and unreliable due to contractors being responsible for reporting. Another shortcoming of the data was that the MOU failed to provide any metrics to evaluate whether goals were being achieved. An MBE owner stated, “if there are no metrics associated with a Community Benefits Agreement than it is purely a political document.”As a result of (1) no measurements to evaluate the deliverables of the process and outcome, (2) no enforcement mechanisms holding contractors legally responsible, and (3) a lack of transparency in sharing data, the agreement failed to hold stakeholders accountable. While there were challenges with the MOU, there were also several wins. One of the biggest wins was the collaboration among institutional leaders and their commitment to equity and inclusion in development, the Urban League, Cuyahoga Community College and the construction industry. Another win is that it provided economic opportunities for Cleveland residents for employment and entrepreneurship. Cleveland’s MOU as well as other prior actions have pressured the government and developers to guarantee more equitable and inclusive development. For example, in 2016, Cuyahoga County implemented a Small Business Enterprise (SBE) Set Aside program, which they regularly report and track the achievement of meeting the ordinance’s targeted goals.

Selection of Recent Development Projects

While many institutional leaders signed onto the MOU, over time the impact of the MOU diminished. After several years of implementation, developers and contractors opted not to sign onto the agreement and instead created their own community benefits initiatives. A few of these projects I discuss below, include Metro Health, the Quicken Loan Arena (aka Rocket Mortgage Fieldhouse), Opportunity Corridor, Sherwin-Williams, and Progressive Field.

Metro Health

Metro Health, as part of its slightly less than $1 billion Eco District plan (aka Metro Health Transformation Project), constructed a new 11-story hospital tower (consisting of roughly 200 patient rooms) and an employee parking garage between 2018 – 2022. In partnership with Metro West Community Development Corporation (CDC), Metro Health built an affordable and market-rate housing project, including housing for older adults, and helped fund social service programs. At a cost of approximately $100 million, Metro Health bulldozed the old hospital site in 2022, and is currently developing the space as a park. All projects have been paid for by hospital bonds, so public money was not used. The Hispanic Contractors Association (with Al Sanchez, Gus Hoyas and Adrian Maldonado & Associates) advocated for Latino/Latina employment and contracting opportunities on the massive hospital expansion project near neighborhoods with a large Hispanic community (i.e., Clark-Fulton and Brooklyn Centre). The negotiations between Metro Health, Turner Construction (the prime contractor), and Hispanic industry leaders resulted in a Letter of Assent to the PLA that requested Turner to help fund the Latino Construction Program. The requirements of the PLA were subcontracting goals of 25% SBE, 7% FBE, and 15% MBE, plus 5% of the 15% MBE requirements set aside for Hispanic-owned MBEs. The PLA’s workforce goals included 20% workers of color, 5% women workers, 40% Cuyahoga County workers, and 20% City of Cleveland workers. Turner Construction monitored the goals of the PLA.The contractors held five outreach events to assist MBEs, FBEs, and SBEs in the procurement process. While the project is still ongoing, as of September 2022, Metro Health’s transformation project have overachieved on all goals: 31.8% SBE, 15.2% MBE, 5.38% Hispanic-owned MBE, and 12.6% FBE.

Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse (aka Quicken Loans Arena)

Dan Gilbert, the majority team owner, and other owners of the Cavaliers proposed renovations of Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse in 2016. The construction consisted of modifying the arena’s entrance and creating more entertainment and dining spaces for guests to socialize inside the arena. In 2016, the state/county/city and the Cavaliers agreed to split the cost of renovations. The Cavs and the public agreed to each pay $70 million for a total estimated cost of $140 million. Because the Cavs agreed to pay over-expenditures if the project went overbudget, the Cavs ended up paying $115 million in construction costs. The public still ends up paying significantly more than the Cavs because Cuyahoga County took out $140 million in bonds for the cost of the project and they will have to pay accruing interest on the bonds. Even with the Cavs $122 million in bond repayments, it was estimated that the public could pay anywhere between $200 - $250 million.There was a great deal of opposition to this project, particularly due to the public paying to renovate a stadium that Dan Gilbert, who is worth almost $20 billion, could easily afford to pay for himself. The public was frustrated that the money was going towards renovating an arena instead of using the same public funds to address social problems and issues within their community.

Using the campaign slogan, “#NotAllIn,” Greater Cleveland Congregations (GCC), the Cuyahoga County Progressive Caucus, SEIU District 1199, and other community groups organized for community benefits for the Cavs stadium renovations in exchange for using public subsidies. The coalition negotiated an initial CBA with the Cavs, which ensured a commitment for a community fund and a certain percentage of work hours set aside for women, people of color, and City residents. The coalition was opposed to the agreement, while other community groups, including Cleveland’s chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Cleveland Building and Construction Trades Council, and the Black Contractors Group, were in support. As the negotiations continued, the City approved the Cav’s renovation plans without a finalized CBA. In response, the coalition collected over 20,000 signatures for a referendum stating that the City must hold off on approving the agreement before CBA negotiations between the community and the developers are final. The City Council refused to accept the petitions, which led to GCC filing a lawsuit against the City. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of GCC and found that the City was obligated to accept the petition. After the lawsuit, Gilbert withdrew his application to renovate the arena. Then GCC made a backroom deal with the Cavs, which many community members were in opposition to, that guaranteed funding for two mental health and behavioral treatment centers, in addition to workforce hiring and Minority-owned and Women-owned Business Enterprise (MWBE) contracting goals. Construction began in 2017 and was completed in 2019.After extensive research, I was unable to determine whether the mental health facilities were built, but the Cavs exceeded all workforce and MWBE goals. Cavs achieved 52% Cuyahoga County hiring goal (actual goal 25%), 24% City resident hiring goal (actual goal 20%), 24% MBE participation goal (actual goal 20%), 6% FBE goal (actual goal 5%). In total, 1,600 workers worked on the project and less than 1% were female workers. Of total contract dollars, 69% was awarded to MWBEs.

Opportunity Corridor

Opportunity Corridor is a 3.2-mile roadway that cost over $300 million project to build. The construction is divided up into three sections, and was overseen and funded through the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT), with input from Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson administration.52 Section 1 project (construction in 2014, 2015, 2017) focused on rebuilding the E. 105th Street starting in University Circle (at Chester Avenue) to Quebec Avenue. Section 2 (construction in 2016-2018) and Section 3 (construction 2018 – in progress), consists of building a new roadway starting from where Section 1 left off at Chester Avenue to the beginning of I-490/I-77 interchange. The project committed to 20% MBE and Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) contracting goals, which means a share of $53.4 million were allocated to either MBEs and DBEs.55 To break down goals even further, contracts were awarded to 8.5% Black-owned MBE ($22.7 million), 1.5% Hispanic-owned MBE ($4 million), 1.5% Asian and Native American-owned MBE $1.5 million, and 8.5% DBE (including FBE) $22.7%.56 The government made a commitment of $500,000 for on-the-job training (OJT) for 80 Cleveland residents from Wards 4, 5, and 6.57 And four of those residents would be able to work on Opportunity Corridor for a combined total of 8,500 OJT hours.58 For all three sections, the contractor exceeded the 20% MWBE contracting goals and OTJ training hours. For Section 1, MWBEs represented 23.69% of contracting awards ($5 million), and Cleveland residents worked 11,200 OJTF hours (goal of 8,500 OJT hours). MWBEs represented 35.95% contract awards ($12.7 million) and Cleveland residents worked 10,635 OJT hours (goal of 10,000 OJT hours). (as of November 2022), MWBEs represented 42.13% contracting awards ($63.5 million), and Cleveland residents worked 31,583 OJT hours (goal of 20,000 OJT hours).

Once the road was completed, the next step is decision-making around the types of projects being developed in the vicinity of Opportunity Corridor. Opportunity Corridor is a low-income majority African American neighborhood, so this is an opportunity to build up social, racial, ethnic, gender equity in the field. Over a hundred residences could be displaced by the governments’ use of eminent domain and the government currently owns three-quarters of the lots in Opportunity Corridor. Some residents have expressed feeling excluded from participating in the planning process and find that local government is not being transparent about the process. Residents have shared their concerns to government that Opportunity Corridor is another development project for people living in the suburbs, so they can commute more easily to University Circle instead of being about increasing economic opportunities for local residents. Residents emphasized the need to continue the positive work of ODOT, including monitoring MWBE contracting and OJT hours to build the infrastructure, and having that same level of transparency moving forward to redevelop the area.

Sherwin-Williams

Sherwin-Williams proposed, in 2020, to build a new headquarters (HQ) in Downtown Cleveland and a research and development (R & D) center in Brecksville.The cost of the project is estimated to be $600 million, and Sherwin-Williams will receive $100 million in public subsidies. Some Clevelanders were upset over the development process between Sherwin-Williams and the government because it has not been open and transparent.The City approved a clause Sherwin-Williams wrote in the development agreement that stated the company could keep certain information/documents “confidential,” which implies that the public is not allowed to have access. Sherwin-Williams also did not share specific MWBEs contracting and targeted-hiring goals upfront or offer any type of community benefits. Sherwin-Williams originally selected ten contracting firms until industry leaders found out that out of the 10 firms none were MBEs. Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Black Contractors Group, the Hispanic Contractors Association, and other leaders in the community protested for community benefits, including workforce hiring and MWBE contracting goals.

Sherwin-Williams established a community benefits initiative that included 4,000 full-time jobs in Cuyahoga County, plus an additional 400 jobs in the future; economic opportunities for women, people of color, and Cleveland residents in employment and contracting; investment in training and education programs for careers in the construction industry; transparency in reporting; working with relevant stakeholders, including the community; hiring an independent agency to monitor achievement of goals; in collaboration with the Urban League of Greater Cleveland, help initiate the Construction Accelerator Program that assists MWBEs in building capacity and capital to grow; and working with the Northeast Ohio Hispanic Chamber of Commerce on a similar initiative. For diverse suppliers working at the HQ site, Sherwin-Williams set aside 15% of contracting awards to MBEs ($70 million), FBEs were awarded 7% of contracts ($33 million), and Cleveland Small Business Enterprise (CSB) awarded 8% of contracts ($38 million). For diverse suppliers working at the R&D site, Sherwin-Williams set aside 30% of contract awards to MWBEs ($84 million). For both the HQ and R&D sites, Sherwin-Williams enacted a 16% worker of color hiring goal and 7% female hiring goal. And for the HQ site only, Sherwin-Williams enacted a 20% Cleveland resident hiring goal.

Progressive Field

Progressive Field is a $435 million renovation project that consists of refurbishing administrative offices; private spaces and facilities for the team; mechanical, electrical, and plumping restorations; improving guest areas; and building additional spaces for guests to entertain, dine and socialize. In public subsidies, the state offered to pay $2 million, the county – $9 million, the city – $8 million for the next fifteen years of the Guardian’s extended lease. The team agreed to pay $4.5 million each year for the next fifteen years. The government also expects to use revenue from the Gateway East parking garage, but if it does not equate to $2 million then they will have to pull money from the general fund, which will take funding from safety and emergency services, etc. The government also plans to use some of the money from the county bond, which was initially set up from the Q Deal, but those funds will run out soon.The Guardians plan to begin construction at the end of the 2023 Baseball season. The Guardians agreed to a 2% Veteran-owned Business Enterprise (VBE), 3% Hispanic-owned MBE, 8% FBE, 18% SBE, and 20% Black or African American-owned MBE contracting awards. Their workforce goals are 45% Cuyahoga County resident, 20% Cleveland resident, 3% low-income resident, 20% worker of color, and 6% women hiring goals. A diverse associate construction manager was added to the team in late 2023. Other community benefits initiatives include, collaborating and partnering with workforce and economic development agencies as well as relevant community stakeholders, building a mentor-protégé relationship, increasing the capacity of MWBEs/SBEs/VBEs, creating a Community Review Group (CRG), and regularly report goals for transparency. The CRG will assist with implementation, monitoring, and transparency of community benefits plan and community members will be represented on the committee.

Summary of Findings

All the projects listed above, including the MOU, had some form of community benefits related to workforce development and entrepreneurship. In all cases there was a lack of community participation in terms of negotiating the model CBA and other community benefits initiatives. Since the community was not involved in the process and the developers had control over creating their own community benefits plans, none of the projects enacted authentic CBAs. To add to this point, since most of these projects used public money, the community should have greater control and influence over the decision-making process around development projects. One of the main pitfalls of having a developer create an agreement on their own is that the community is less likely to be engaged in implementing, monitoring, and evaluating it. All developers regularly reported meeting goals; however, I was unable to find workforce data on the Metro Health Transformation project and real data, other than commitments, for Sherwin-Williams. Three out of the five developers established monitoring committees, but two committees used an independent agency to monitor and only one included community members on the committee. While the community has or will receive some benefits from the project, the process needed to be more open to the community so they could advocate for greater benefits and mitigate potential harms of the projects.

Recent DEI Initiatives

Other recent and related actions to foster a more diverse workforce in the construction industry in Cleveland include:

- CEA, Cleveland Building & Trades Council, and other trades and construction contractors associations launched Cleveland Builds in 2021. Cleveland Builds is an apprenticeship readiness program, which has already shown early signs of success.

- In January 2023, City of Cleveland approved the allocation of roughly $10 million from the City’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) dollars to the Ohio Means Jobs Cleveland-Cuyahoga County for the “Built Environment” Workforce Development program. The program intends to train 3,000 individuals with a primary focus on people of color and women in the construction industry and provide financial and program/services support for MBE contractors.

Conclusion

It is important that industry leaders learn from these past DEI initiatives, including Cleveland’s MOU, because Cleveland’s City Council and the Mayor’s Office are building off these efforts to propose a city-wide CBO.84 Aside from the Fannie Lewis law, Cleveland’s MOU and the community benefits initiatives mentioned above had no teeth. In other words, there was no strong enforcement mechanism to hold the developers, the contractors, and all relevant stakeholders accountable. In addition, there was limited community participation in developing the MOU and advocating for community benefits for all publicly-subsidized development projects. One of the main lessons learned from prior DEI initiatives in Cleveland is that for CBAs and CBOs to be successful the culture (e.g., construction industry, politics, developers, urban planning, etc.) needs to change and people need to be intentional about fostering greater diversity and inclusion. In my next article, I will expand on the elements needed to have an effective CBO. I will offer best practices in pursuing democratic citizen participation and achieving equity in the construction industry and development.

Written By: Athena Nicole Last

Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Sociology at Syracuse University studying CBA campaigns in the Rust Belt region.